| By Paulo Martins. University of Mihno, Braga, 11/11/2021 |

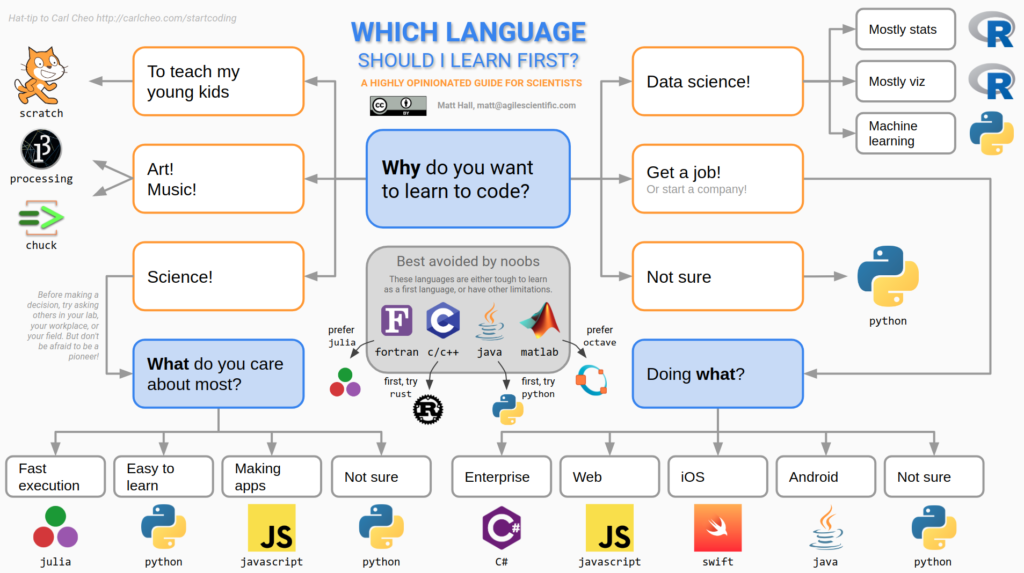

Learning a programming language

Coding literacy

Learning a programming language is easier than learning a natural language (?), explore new scientific strategies, automate daily tasks, boost problem solving skills.

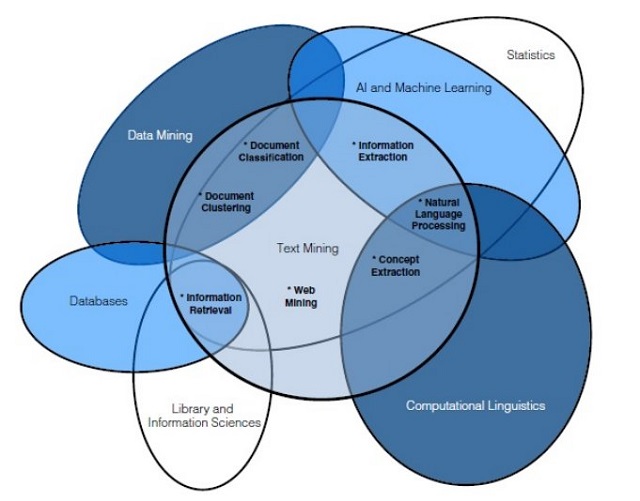

NLP and data science

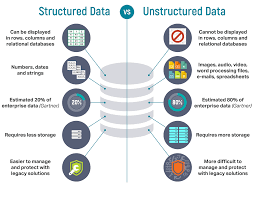

Data: raw, unstructured vs information: structured, organized…useful.

Some tools

Webcrawlers: fetching comments is challenging (javascript and stuff)

Json files Json syntax

YAGO is a knowledge base, i.e., a database with knowledge about the real world. YAGO contains both entities (such as movies, people, cities, countries, etc.) and relations between these entities (who played in which movie, which city is located in which country, etc.). All in all, YAGO contains more than 50 million entities and 2 billion facts.

YAGO arranges its entities into classes: Elvis Presley belongs to the class of people, Paris belongs to the class of cities, and so on. These classes are arranged in a taxonomy: The class of cities is a subclass of the class of populated places, this class is a subclass of geographical locations, etc.

YAGO also defines which relations can hold between which entities: birthPlace, e.g., is a relation that can hold between a person and a place. The definition of these relations, together with the taxonomy is called the ontology.

SPARQL, GraphDB